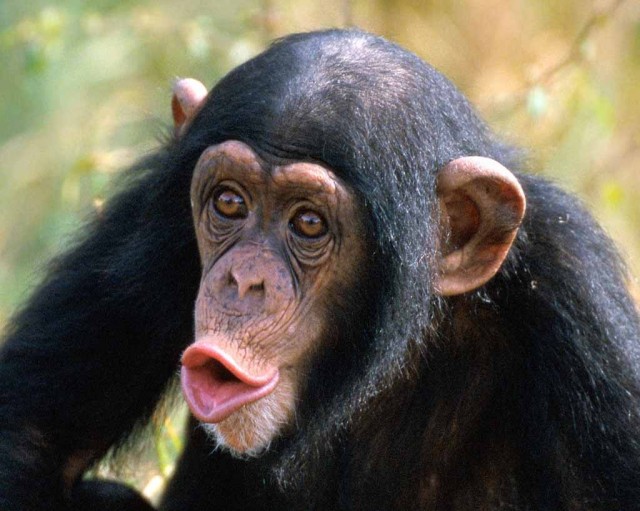

Crime, punishment and chimpanzees

By / Los Angeles Times

Published: September 01. 2012 4:00AM PST

Despite being one of the closest living relatives to humans, chimps lack the urge to punish thieves who are caught red-handed, unless they themselves are the victims, according to a study published Tuesday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In a series of experiments involving 13 furry subjects with names like Frodo, Natascha and Ulla, the animals showed no interest in intervening when they observed a fellow chimpanzee purloining grapes and food pellets from a third chimp.

It was only when a chimp had their own treats stolen that they got angry and took action — in this case, by opening a trapdoor on the miscreant.

The study, according to lead author Katrin Riedl, a developmental psychologist with the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology, in Leipzig, Germany, suggests that the practice of punishing thievery and crimes committed against others is a uniquely human trait.

“Punishment can help maintain cooperation by deterring free-riding and cheating," wrote study authors.

“Of particular importance in large-scale human societies is third-party punishment in which individuals punish a transgressor or norm violator even when they themselves are not affected."

“Overall, chimpanzee punishment appears confined to retaliation against personal harm when the punisher is in a position of dominance," wrote study authors. “Chimpanzee punishment is of the ‘might makes right’ variety."

In a series of experiments involving 13 furry subjects with names like Frodo, Natascha and Ulla, the animals showed no interest in intervening when they observed a fellow chimpanzee purloining grapes and food pellets from a third chimp.

It was only when a chimp had their own treats stolen that they got angry and took action — in this case, by opening a trapdoor on the miscreant.

The study, according to lead author Katrin Riedl, a developmental psychologist with the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology, in Leipzig, Germany, suggests that the practice of punishing thievery and crimes committed against others is a uniquely human trait.

“Punishment can help maintain cooperation by deterring free-riding and cheating," wrote study authors.

“Of particular importance in large-scale human societies is third-party punishment in which individuals punish a transgressor or norm violator even when they themselves are not affected."

“Overall, chimpanzee punishment appears confined to retaliation against personal harm when the punisher is in a position of dominance," wrote study authors. “Chimpanzee punishment is of the ‘might makes right’ variety."

k

k

New research suggests that chimpanzees do not engage in third-party punishment.

Great apes are capable of an advanced cognitive ability.:Chimpanzees:

1. they plan ahead,

2. they exhibit altruism, and

3. some have incredible memory skills.

Most recently, researchers asked whether chimpanzees exhibit a sophisticated social behavior called “third-party punishment.”

This behavior occurs when one individual punishes another individual for a transgression that did not directly harm the punisher.

So in a chimp's case, it might involve an individual punishing a fellow group-member for stealing food from a different group member.

The behavior is considered cognitively advanced, as the punisher must not only understand that the transgression was unfair despite not being involved, but must also be willing to incur some cost and no immediate material gain from the punishment.

Third-party punishment is seen often in human societies, and is thought to maintain cooperation by making cheating costly.

Because chimpanzees live in large, complex social groups, they have evolved incredible social skills, and researchers thought it was possible that they might demonstrate this type of behavior.

During each trial in the experiment, separate but adjacent cages held three chimpanzees: the “thief,” the “victim,” and a third individual, one that had the ability to dole out punishments.

The researchers dropped food onto a tray into the victim’s cage, and via a pulley system, the thief could pull this food-laden tray into his own cage.

Once the food was stolen from the victim, the third individual had the opportunity to collapse the tray that was now in the thief’s possession, making the food disappear and thereby punishing the thief for his unfair behavior.

As controls, the experimenters also tested scenarios in which the experimenter moved the food to the thief’s cage (rather than the thief stealing it), the experimenter took the food and placed it in an empty cage, and one where the thief could take food without affecting the victim.

If the potential punisher collapsed the tray only in situations where the thief took possession of the victim’s food, the study could conclude that third-party punishment does exist in this species.

Given the opportunity, the potential punisher did not collapse the food tray significantly more often when the thief had actually stolen the food from a victim than in the other situations.

There were two possible explanations for these results: either the chimpanzees didn’t understand the scenario, or they simply don’t exhibit third-party punishment.

To distinguish between these possibilities, the experimenters also ran second-party punishment trials, where there were only two chimpanzees involved: a thief and a victim capable of punishment.

The difference from the previous trials is that here, the potential punisher was also the victim.

In these trials, the chimpanzees were quick to punish the thief by collapsing the food tray (but only if they were socially dominant to the thief).

These results suggest that, although chimpanzees understand unfair behavior and retaliate when they are personally affected, they do not engage in punishment when they are merely a bystander.

It appears that, for chimpanzees, punishment may function to coerce others into complying, rather than to discourage unfair behavior.

Crime, punishment and chimpanzees | | The Bulletin

http://www.bendbulletin.com/article/20120901/NEWS0107/209010367/

Kate Shaw / Kate is a science writer for Ars Technica. She is a Ph.D. candidate in Zoology and Ecology, Evolutionary Biology and Behavior at Michigan State University, though she's spent much of her graduate career living in a tent in Kenya.

http://arstechnica.com/science/2012/08/crime-and-punishment-chimpanzee-style/

No comments:

Post a Comment